You are here

Patient Power Through Records

Author:

Adam Tanner

Date Written:

January 7, 2017

Published By:

The Boston Globe

Archived News Story:

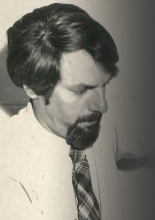

A half a century ago, Harvard Medical School professor Dr. Warner Slack grew disturbed by the disorder in which physicians gathered and stored notes about patients.

If people could access their health histories, he reasoned, they would be more involved and better informed in making decisions for themselves. In the flowery language of the 1960s, he promoted what he called “patient power.”

The key, he thought, was computerization.

Slack’s approach, which he inaugurated in the mid-1960s in Wisconsin, drew on 450 computerized questions, presented according to how a patient responded. Users sat at an elevated keyboard, as tall as a box of tissues, and looked at a tiny screen — really a cathode-ray oscilloscope — a few inches wide surrounded by rectangular slats to reduce glare. Reel-to-reel magnetic tapes, a sign of high-tech brains in that era, spun above in front of a wall of machinery.

Today, electronic medical records are ubiquitous — 87 percent of US office-based physicians were using them by the end of 2015, up from 42 percent in 2008. Yet the rapid adoption of the technology, spurred by $35 billion in federal government incentives, hasn’t proved the cure-all that tech evangelists promised. Electronic records are still difficult for patients to access, difficult for doctors to share among themselves, and difficult to standardize. As recently as last month, President Obama signed new legislation that included provisions designed to help improve interoperability of health records systems.

From doctors’ legendarily bad penmanship to encrypted digital charts, there’s central tension between information technology and medicine — sharing information can be useful, but hoarding information can be lucrative.

The dream of electronic medical records long predates the Internet era. One of the first patients to use Slack’s program on LINC (for Laboratory Instrument Computer) was an elderly man recovering from a heart attack. He diligently worked through the questions, laughing out loud at some of the humorously phrased items Slack had inserted to lighten up the process. “You know, I really like your computer better than some of those doctors over in the hospital,” he told Slack afterward. “For one thing, I’m sort of deaf and have trouble hearing them.”

If someone who may have been born in the 19th century embraced the technology, its future looked bright. Slack’s work attracted national attention, including a television documentary called “LINC with Tomorrow.”

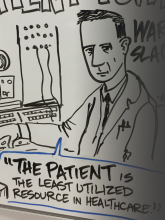

“There is a human traffic jam in the doctor’s office today,” narrator David Prowitt says in that program. Waving a binder in his hands, he highlights the importance of getting patients to describe their health issues. “The medical chart. Hallowed in theory. Often disappointing in practice. Mistakes here can lead to serious trouble later on. Faulty diagnosis, incorrect treatment, possibly death,” he continues. “We’re at the University of Wisconsin Medical Center where researchers have developed an exciting new weapon to attack this problem.”

The camera pans across the computer, and the announcer approaches Slack, who is wearing a crumpled oversized jacket and has a crew cut, seated to the side.

“Warner, you seem pretty comfortable talking to a machine. How does the average patient take to it?”

“Well, it’s really no problem. Actually the LINC is quite sociable as far as computers go,” Slack says with a smile.

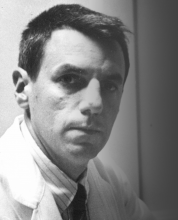

Prowitt puts LINC to the test and answers his own medical questionnaire, pondering a few seconds at each screen. The well-groomed announcer works his way through screen after screen of black and white flickering sentences in all caps, generating a click with every response, “FOR ABOUT HOW MANY YEARS HAVE YOU SMOKED AND INHALED?” the machine asks.

Prowitt, who is in his early 30s, types in two digits, 15.

Slack adds some additional information from his own observations such as how well Prowitt responded to his reflex test. The doctor then takes out a needle and draws blood. After a teletype printer noisily punches out a summary of the results, including his cholesterol reading, Slack reviews its findings.

“I’ve been looking at your record, and it’s normal except for one thing. I must agree with LINC on one point here.”

The television announcer arches his brow as he awaits the doctor’s assessment.

“You smoke too much.”

“Agreed. No arguments at all.”

After that diagnosis, Slack predicts a future of small, cheaper standalone computers in doctors’ offices as well as terminals linked to online central computers to access unprecedented expertise.

Such a vision may seem unexceptional. Yet many in medicine did argue with Slack and scoffed at the idea of giving patients more say in matters they knew little about. Others thought patients would be forced to make complicated medical decisions, whether they wanted to or not. “That wasn’t what I was saying, that the patients should be doctors,” Slack said. “I was saying that we, as doctors, should be providing the patient with as much information as we can but the patient should be, if she or he wanted to be, in charge of her value systems and decide: Maybe I’ll wait, maybe I’ll do it.”

Yet half a century of efforts, including from tech giants such as Google and Microsoft, have yet to realize the vision of patients easily accessing their own complete medical records.

Even Neal Patterson, the cofounder and CEO of Cerner, which operates a major electronic health record system, complains his family cannot access their own records. His wife has suffered from breast cancer since 2007 and visited 35 different providers across the country for treatment, yet has to carry around her records by hand, he told a Senate committee in 2015. Patterson may have to do the same himself: He announced in 2016 that he was diagnosed with soft tissue cancer.

“I think it is a failure of all of us to have in 2015 the fact that Jeanne carries shopping bags to all of her appointments where she is going to see a new doctor or specialist,” he told senators. “If it is you or your loved one and that information is vital, I consider it immoral for people to block that data and force us to carry it in bags.”

The question is obvious: After billions of dollars of government spending in recent years to encourage the digitization of medical data, why does this straightforward goal remain elusive?

Some experts say certain electronic records system providers, hospitals, labs, and others are more interested in wedding customers — and their health care dollars — to their own particular systems rather than addressing the puzzle of interoperability.

“Some health care providers and health IT developers are knowingly interfering with the exchange or use of electronic health information in ways that limit its availability and use to improve health and health care,” the Obama administration’s Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology wrote in a 2015 report to Congress. “This conduct may be economically rational for some actors in light of current market realities.”

Paradoxically, patients cannot access their own lifetime medical dossiers, while for-profit companies have succeeded in building anonymized dossiers on hundreds of millions of patients, gathering information from electronic health records, prescriptions, insurance claims, and lab tests. Such information helps pharmaceutical companies advertise and market drugs.

Some experts blame one of the major electronic health records companies, Epic, which was started in 1979 by one of Warner Slack’s former University of Wisconsin students, Judy Faulkner. Today her company is such a success that she is personally worth $2.2 billion, according to an estimate from Forbes.

In a rare interview, the Epic founder said such charges are unfair and that the government and various committees need to organize electronic health system vendors to agree on common standards. As an example of the complexity involved, she said Epic breaks down the world of health into 150,000 data codes. Industry standards exist in some areas such as medications, but not others such as allergies.

“Is it a rash, is it fever, is it throwing up, is it you practically die? One group may have 87 different ways of putting down reactions to allergies, someone else may have 12. How do they map into each other?” Faulkner said.

When asked how long it might take until all these different systems speak a common language, Faulkner left open the possibility that it will never happen.

“We did not set up a business model where it made sense for Epic to invest their own money figuring out how to talk to and connect to the hundreds of other vendors that are out there,” said Julia Adler-Milstein, a University of Michigan expert on health care IT. “That would have been very expensive, and it is not clear that it would have really benefited their bottom line.”

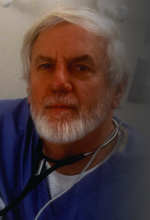

Slack, who is still sharp and active in his 80s, remains confident that eventually patients will gain easy access to their complete records to help in their treatment.

“I’m disappointed that patients are not benefiting more,” he said. “Once the Internet came — doctors were saying patients won’t be willing into interact and, of course, we disproved that.

“I’m not sure I was ever predicting it would be easy,” he added. “This will come.”

Adam Tanner is writer in residence at Harvard University’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science. This article is adopted from his new book, “Our Bodies, Our Data: How Companies Make Billions Selling Our Medical Records.”